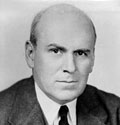

| In

C. Wright Mills’s 1956 book, “The Power

Elite,” John J. McCloy was characterized as the

epitome of the behind-the-scenes establishment that

ran America. His career in government began in 1917,

when, as a 22-year-old lawyer in the Justice Department,

he was assigned the task of investigating the 1917 Black

Tom munitions explosion in Hoboken, N.J. Through brilliant

investigative work, he identified it as German state-sponsored

terrorism. He then moved back and forth between the

private sector and government, serving as assistant

secretary of war, president of the World Bank, high

commissioner for Germany, and finally, under President

Kennedy, as disarmament adviser. President Lyndon Johnson

chose him to represent the private sector on the Warren

Commission.

I met McCloy at 2:35 PM in his office on the 46th Floor

of the Chase Manhattan Bank, of which he had been chairman.

He was now, in his early seventies, a senior partner

at the corporate law firm of Milbank Tweed Hadley &

McCloy., As he rose slightly to greet me, his body seemed

much too small for his massive head. He asked his secretary,

a Miss Wilson, to hold all his calls.

He began the interview by telling me that he viewed

his appointment to the Warren Commission as a continuation

of his government service. He joked that since he was

unemployed at the time, unlike the four Congressional

members of the Commission, he had time to attend all

of the hearings in which witnesses had testified. He

leisurely told me how his work on the Black Tom had

led him to believe that an investigation should have

its own investigators. So he convinced Chief Justice

Warren to set aside the FBI report and organize an independent

investigation staffed by young lawyers.

I asked him why he opposed using FBI agents for the

investigation. He replied coolly, “J. Edgar Hoover

likes to close doors. I told Warren we had to re-open

them.”

Had the commission’s investigation faced limits

in what it could report?, I asked.

He answered by describing Thornton Wilder’s novel

“The Bridge Of San Luis Rey,” in which an

investigation uncovered a series of sexual liaisons.

He compared the book to the investigation, saying, “We

had uncovered a lot of minor scandals, but they were

not relevant to our investigation. We decided not to

publish them in the report.”

When I pressed him on what these scandals involved,

he replied, “It was as if someone picked up a

rock and the light caused all sorts of bugs to run for

cover.” He said the Secret Service needed to obscure

indiscretions of its agents the night before the assassination,

the FBI had to expunge embarrassing incidents from its

reports, and the CIA had to hide its domestic activities.

He added that even Attorney General Robert Kennedy,

the president’s brother, had put his own man,

Howard Willens, on the staff, to deal with “inappropriate

revelations.”

I had already interviewed Willens at his office at the

Justice Department, and he had told me that the attorney

general had dispatched him to the commission to make

sure it had assistance from the Justice Department,

but he said nothing about suppressing any material.

So I asked McCloy about what Willens had done.

“He locked away material in his desk,” he

replied. According to McCloy, Willens did not believe

the staff had any need to see it. He said it concerned

a “national security issue” he was not free

to discuss.

I asked whether the commission had fully explored Oswald’s

foreign connections.

He said that he himself believed there was persuasive

evidence that Oswald had been trained in espionage and

that Oswald might have been “a sleeper agent who

went haywire.” He said Warren did not buy his

theory, and he lost the argument because “Warren

was, you need to understand, stubborn as a mule.”

|