|

When I stopped my car on an icy night in Ithaca, in

January 1966, to give an elderly woman a ride up the

hill to the Telluride House, I could not have known

that a subsequent misconception about this brief encounter

with a stranger would result three months later in the

publication of my first book, “Inquest: The Warren

Commission and the Establishment of Truth.”

The chain of odd events began earlier that afternoon

when I received a phone call from Felker, who was then

working as a consulting editor at the Viking Press at

New York. Only a week earlier, he had told me the good

news that Viking wanted to publish my book on the basis

of the 90-page draft that I had sent him.

Now it was bad news he relayed. He said that since my

book was very short, Viking was, as he put it, “toying

with the idea” of combining my draft with two

other essays, one by Leo Sauvage, a French correspondent

for Le Figaro, the other by Fred Cook, an investigative

reporter for The Nation, and entitling the anthology

“New Doubts About The Kennedy Assassination.”

When I responded that such a combination might confuse

the issue, Clay said that he personally agreed with

me but that Tom Guinzburg was concerned that, as an

undergraduate at Cornell, I lacked sufficient credentials

to take on alone such a sensitive matter as the Warren

Report.

“I see,” I said, ending the dispiriting

conversation. I stopped working on Chapter X, the last

chapter, and, despite the freezing weather, headed downtown

to see a new movie, “Mickey One.” Alas,

Arthur Penn’s film about a comic who becomes gradually

involved with merciless killers failed to cheer me up.

It was on the drive back home that I encountered the

elderly woman. She was bundled up in a heavy shawl,

vainly attempting to hail a taxi at the bottom of the

State Street hill. Realizing she had little chance of

finding one, I asked whether she would like a ride up

to the Cornell campus. When she got in the car I recognized

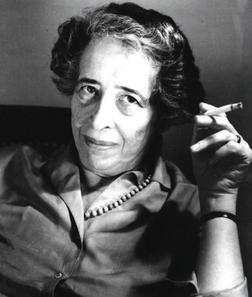

her as Hannah Arendt. She had been featured in a profile

the week before in the Cornell Sun, and had long before

established herself as one of the leading intellectuals

in America. Her reporting in The New Yorker on the war-crimes

trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, in 1961, also

had made her the center of a controversy over the role

of Jewish leaders in the Holocaust, and now she was

a visiting professor at Cornell, giving a course called

"From Machiavelli to Marx."

Just a few days earlier, I had audited her lecture on

the accused Soviet spy Alger Hiss. Although she retained

her German accent, her English was precise. I told her

how impressed I was by her critique of the FBI’s

identification of Hiss’s typewriter, but, still

half-frozen, she remained silent. Then, halfway up the

mile-long hill, as the car skidded dangerously on the

ice, perhaps terrified by my driving she asked me whether

I was an undergraduate at Cornell. I answered affirmatively,

then added that I was also a hopeful author, and that

Viking was interested in publishing my thesis on the

Kennedy assassination. She then told me that Viking

was her publisher, too, and asked me when my book would

be published.

I told her that although Viking had agreed to publish

it as a book, it was now considering publishing it merely

as part of a three-author anthology. She said, in her

heavy German-inflected voice, “That is reprehensible.

They can’t do that,” and offered to ask

her editor there, Denver Lindley, to intervene. I then

dropped her off at the Telluride House, where she was

staying.

The next morning, January 14th, I went to Arendt’s

office in Boardman Hall. She looked confused, asking,

“Who are you?” I reminded her of my problem

with Viking and her kind offer to call her editor there.

She shrugged, dialed a number in New York, and asked

for Denver Lindley. When her editor came on the line,

she said, “I have a student here,” then,

holding her hand over the receiver, asked me my name,

which she relayed to Lindley. She then told him I had

received conflicting versions of how Viking planned

to publish my book. After hanging up, she told me that

Lindley knew nothing about my book. That was the last

time I saw Hannah Arendt.

The next week Aaron Asher, a senior editor at Viking,

called to tell me he was editing my book and that I

faced a tight production schedule since Viking planned

to publish it in three months. When I asked him about

the anthology, he answered that there had never been

a thought given to an anthology. He explained that Felker

worked there only one day a week and had mixed up my

book with an agent’s proposal for another book,

which Viking had turned down. So ended my concerns.

I left Cornell for Harvard, where I was enrolled in

the Government PhD program, and, true to its word, Viking

published my book in April 1966.

More than nine years later, on December 5, 1975, still

in Cambridge, I received a call from Aaron Asher, who

told me in a hushed voice that Hannah Arendt had died

and that he expected her “protege” would

surely want to fly to New York for her funeral service.

I told him that not only was I not her protege, but

that I had met her only twice in my life. Taken aback,

Aaron then told me what had actually happened at Viking

a decade earlier. Clay Felker had been correct: Tom

Guinzburg had not wanted to publish my book because

I was an unknown commodity. But in the middle of an

editorial meeting Lindley had been called to the phone,

and when he came back, his face beet-red, he’d

shouted at Guinzburg, “You can’t do that

to Epstein. He is Hannah Arendt’s student. Her

protege.”

Guinzburg replied, “If she vouches for him, there

is no reason not to go ahead with publishing the book.”

A fortunate misunderstanding– at least for me.

|